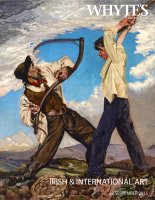

18

Aloysius C. O’Kelly (1853-1936)

BRETON FIGURES IN AN ORCHARD

oil on canvas

signed lower right

25 x 20_in. (63_ x 52.71cm)

Provenance: Nadeau’s Gallery, Connecticut, USA;Private collection

As a republican Realist, Aloysius O’Kelly operated in multiple colonial circumstances, exploring underlying connections

between ethnicity, history, religion, land and culture. In Ireland, he adopted a radical role that projected the west of

Ireland as the repository of the social values of the imagined nation. His interests were aesthetic, but also political,

ideological and humanitarian. Although aesthetically he remained loyal to the conventions of Realism, he was politically

the most radical Irish artist of his era. The difficulty of matching his political opinions to his artistic calling, however,

resulted in many stylistic swerves in his career: Realist in Ireland, Naturalist in France and Orientalist in North Africa.

He was one of the first Irish artists to discover Brittany in the 1870s. In summer, the artists arrived laden with knapsacks,

canvases and easels from the Parisian academies. The villages resembled gigantic studios and the villagers posed in

their picturesque costumes, providing the distinctive note so prized by painters. In Brittany, the artists went native

themselves, wearing long hair, old paint-stained corduroy suits, battered hats, flannel shirts and wooden sabots stuffed

with straw.

O’Kelly was an acute observer of Breton dress - its evolution over a fifty-year period can be observed in his work. Breton

women wore distinctive white linen coiffes and wide collars, dark skirts, fitted bodices, embroidered waistcoats and

heavy wooden sabots. The ethnographer, René-Yves Creston, has identified sixty-six styles of Breton dress, including over

1,200 different kinds of coiffe, revealing clearly articulated relationships of locality, wealth and kinship.

The aesthetic of modernity engaged few Irish artists in France, but O’Kelly reconciled a range of styles derived from

both traditional and avant-garde art, blending academic, realist and plein-air elements into an innovative mode of rural

naturalism. His true originality, however, lies in his representation of communities in transition; in Brittany, he portrayed

the social evolution over a fifty-year period - from acute poverty to an industrious people.

Many accounts of the Breton peasantry in the late nineteenth century describe a wild, unwashed people who roamed

the countryside, barefoot, dressed in long goatskins, terrorizing effete Parisian artists with their wild cries and primitive

ways. The women were supposedly of great beauty (but dubious virtue), and the men of obduracy and chauvinism.

O’Kelly dignifies them, as he did the peasants of the West of Ireland.

Repeatedly drawn to the rural periphery, O’Kelly countered the primitivist stereotyping of many of his contemporaries,

as in works such as this.

As O’Kelly’s paintings of Brittany are predominantly peopled, they encourage the viewer to engage with the social issues

and ways of life of the time. The naturalist aesthetic, propounded by Émile Zola, advocated a documentary approach

to the study of contemporary life. Objectivity and verisimilitude were considered premium virtues, but were to be

tempered by a sense of immediacy. Although O’Kelly performed this social documentary style in many of his Irish works,

in Brittany, he blended a rural naturalism with a form of Impressionism, without ever relinquishing the lessons learnt in

the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme with whom he studied in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

In this painting, one of a series with the same figures, in the same setting, O’Kelly shows an awareness of contemporary

Impressionist trends in art. He is less interested in the characterisations of the figures as individuals, than in setting

them in a landscape, saturated with colour. The series includes Respite from the Midday Sun/Noonday in the Fields

(Royal Society of British Artists in 1886/7). Here the standing figure, arm around the tree, stresses the vertical axis of the

painting, in contrast to the other versions which have a distinct horizontal emphasis. Across the series, the iridescent

landscape shimmers in the sunshine.

Prof. Niamh O’Sullivan

August 2015

IRISH & INTERNATIONAL ART · 28 SEPTEMBER 2015