38

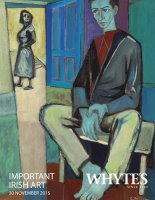

Gerard Dillon (1916-1971)

PORTRAIT OF DAN O’NEILL, 1952

oil on canvas

signed lower right; with Dawson Gallery framing label on reverse

22 x 18in. (55.88 x 45.72cm)

Dawson Gallery, Dublin;The Collection of the late Jim O’Driscoll SC;Thence by descent

Possibly exhibited at ‘Gerard Dillon, Early Paintings of the West’, Dawson Gallery, Dublin, 4-27 March 1971, catalogue no.

10 as Dan O’Neill;’Gerard Dillon, A Retrospective Exhibition’, Ulster Museum, Belfast and Municipal Gallery of Modern Art,

Dublin, 1972;’Gerard Dillon (1916-1971), A Retrospective Exhibition’, Droichead Arts Centre, Drogheda, 23 January to 20

February and Linen Hall Library, Belfast, 27 February to 21 March 2003, catalogue no. 24 (loaned by present owner)

Gerard Dillon’s Portrait of Dan O’Neill was painted in 1952, and is, therefore, a work from a key point in his career. By this

time, Dillon had established himself as a painter and was closely involved in many of the exhibitions and organisations

promoting and supporting visual art in Ireland North and South. He would go on to represent Great Britain in the

Pittsburgh International exhibition in 1958 and the Guggenheim International, where he represented Ireland in 1958

and 1960. (1) This unusual portrait, which positions the figure of painter Daniel O’Neill within a slanting and disjointed

domestic space, is given a broader narrative context, provided by the figure of the woman, glancing askance through an

open door. Gerard Dillon was born in Belfast in 1916, and left school in 1930 initially to work as a painter and decorator.

Largely self-taught as an artist, he lived in London until the outbreak of war in 1939, when he moved to Dublin. Dillon

had visited Ireland throughout these early years in London, and was particularly influenced by the landscape of

Connemara, returning there to paint throughout his career. Moving to Dublin in 1939, however, meant that he became

part of a pivotal time in the capital’s artistic and creative history. Dillon was influenced by the White Stag group, formed

by leading experimental Irish and émigré artists and was involved in the establishment of the Irish Exhibition of Living

Art. (2) His circle of friends and fellow artists included Nano Reid and Mainie Jellett, as well as fellow Belfast painter,

Daniel O’Neill, the subject of this portrait. Dillon met O’Neill in 1940, and they often worked and exhibited together. In

her entry on O’Neill in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, Carmel Doyle notes that ‘together they carved images on stones

retrieved from the wartime blitz in Belfast’. (3) Dillon and O’Neill both exhibited with Victor Waddington in Dublin, and

at Deirdre McDonagh and Jack Longford’s Contemporary Art Galleries. (4) The central figure in Portrait of Dan O’Neill

occupies the right-hand side of the canvas, seated on a four-legged stool. His body appears too large for the space,

and he leans forward slightly. This seated, frontal pose, turning slightly towards the light of the doorway, together with

the sinuous black outline of the figure against the background and the stylised treatment of the folds of fabric over his

body, reflects the influence of early Christian stone carving and manuscript illumination on Dillon’s work. It also, perhaps,

reflects the influence of European painters like Georges Rouault (1871-1958), whose work had been at the centre

of a Dublin controversy in 1942, ten years before this work was completed. In contrast to the stylised and flattened

treatment of the space in which the figure sits, and his clothing, Dillon has rendered the hands, feet and facial features

with great sensitivity and nuance. This focus on the bare flesh, rendered in vivid turquoise, together with the troubled

and troubling expression on the figure’s face, creates an atmosphere of anxiety and doubt. While this is a portrait, the

inclusion of the female figure outside the door establishes a narrative of tension within the picture. It is possible that

this figure represents Eileen Lyle, whom O’Neill married in 1942. This tense atmosphere is reflected in the fragmented

treatment of the interior space in which the figure sits, with its disjointed perspective, and planes of vivid colour sliding

toward the foreground. This Expressionist treatment of the interior could, perhaps, be read as a further expression of the

lack of accord between the two figures, collapsing the boundary between the interior world of the individual and the

exterior environment in a way that foreshadows his later dream-like Pierrot paintings, produced in the final years of his

life. (5)Dr Niamh NicGhabhannNovember 2015

IMPORTANT IRISH ART · 30 November 2015